Transcriptions of A Dolphin Pod

Okay, so they’re technically my original scripts rather than true transcriptions. There might be a word different here or there or an improvised on-mic joke you’ll miss but the message is the same.

Episode 1 – The Dolphin from the Black Lagoon

Welcome to A Dolphin Pod. I’m Amy Grisdale. I’m a stand-up comedian, marine biologist and writer for This Paranormal Life, which is an excellent podcast you should all definitely listen to. After this one, of course. Because I’ve actually got something really important to tell you about. Dolphins.

I’ve always been fascinated by them. I grew up watching them in shows at aquariums and marine parks. They were always popping up in movies and on TV, hanging out with people, doing tricks and looking really really happy. It seemed totally normal and I didn’t question it for a second. It wasn’t until much later in life that I started to realise things aren’t the way they seem.

I don’t think dolphins are happy in captivity. And hey, just because I’m a marine biologist specialising in dolphins doesn’t mean I’m biased in any way. I’m here to present you with the facts. For example, did you know that dolphins are basically the best animals on Earth? Fact. Trust me, I’m technically a scientist.

But seriously, I’ve done everything I can to make sure the information you’re about to hear is thoroughly researched and correct to the very best of my knowledge at this point in time.

At the end of the day, this podcast is just one person’s perspective. You can take it or leave it. Except please do take it because it’s true and I spent a year of my life on this podcast.

Dolphins are incredible animals. They spent 50 million years evolving into savage ocean predators and along the way, they developed some of the most interesting brains known to science. Also, they’re adorable. Just look at them. They are the thing I care the most about and the reason I studied marine biology in the first place. But once again, I’m not biased.

Even after saying all that, on the face of it this episode isn’t about dolphins. It’s about one specific dolphin. But before I can properly introduce you I need to fill you in on some back story. Or rather, some forward story. In terms of the timeline we’ll be starting somewhere in the middle and jumping around quite a bit so best to hang on tight.

A couple of years ago I was re-watching one of my favourite classic films. The Creature from the Black Lagoon. If you haven’t seen this film – where’ve you been, mate? It’s been out for 60+ years at this point. Even if you’ve never heard of it I’m willing to bet if you saw a picture of the actual creature you’d recognise it.

He’s the quintessential swamp monster, have a look at the photo gallery on adolphinpod.com or follow @adolphinpod on Instagram if you have no idea what I’m talking about. Like any good nerd I was reading the IMDB page as I was watching the movie and I came across a little nugget that led me down the oceanic trench that became this podcast.

We’re starting on the set of the Creature from the Black Lagoon. It was a universal production from 1954 and today it could be one of the most-loved classic creature features of all time.

But it wasn’t seen as a masterpiece when it was made. It was criticised for being another of a long string of Hollywood horrors that all copied one another. Good thing the horror industry is nothing like that today.

There’d already been The Thing, The Wolf Man and The Mummy (not the Brendan Fraser one). But even though the critics were dragging it through the mud calling it hack, audiences liked it a lot. It grossed $1.3 million in theatres, which is the equivalent of nearly $14 and a half million today.

If you want some context on that, the best selling films in 1954 were Rear Window and White Christmas, each of which pulled in $25 million or so. I know of both but have seen neither so how successful are they really?

On balance, the Creature From the Black Lagoon didn’t do that well. But as I mentioned, people liked it and it has stood the test of time. I think it’s a good film at least. If you don’t already know what happens, it’s about a team of scientists that stumble across an unusual fossil deep in the Amazon.

It’s a webbed hand left by what they assume to be an extinct creature. As it turns out, he’s still alive and - spoiler alert - goes on a murderous rampage.

I have to say, it really holds up. It’s worth a watch. One of my favourite things about it is how earnest the scientists are. It’s made very clear that the characters’ motivation is the pursuit of knowledge and there’s a healthy dose of nerds being excited about rocks which I find very endearing.

There are so many parts where it’s obvious the writers did their homework. They talk about evolution and natural selection and really nail it. When the characters go SCUBA diving in the black lagoon, which is a bad idea by the way, they make a point of talking about safety stops before surfacing.

They didn’t need to add that in, but I guess they wanted to represent it in a realistic way. One of my pet hates is when films and TV shows purposely ignore established realities. Like yeah, there’s a monster on the loose but hold your horses because if you rush to the surface too quick you’ll get the bends.

And if you squint the film still looks great. Seriously, it’s not that bad. And a lot of that is to do with the creature’s costume, which was pretty revolutionary for the 50s. It had a mechanism built into the arm that the stuntman inside could pump to make the gills ripple and move the creature’s mouth.

According to the cast list there were actually two creatures from the black lagoon. Whenever you see the monster on land the person inside is an actor called Ben Chapman.

The costume’s eyes were made of really thick green rubber, which looked incredible from the outside but the poor sap inside could barely see. In a scene where he had to carry his co-star Julie Adams into a cave, he accidentally smashed her head into a wall and knocked her unconscious. She did all of her own stunts for the film, a decision she thankfully lived to regret.

While we’re talking about Julie I just have to say she is wonderful in this film. I’d say she’s the most natural of all the characters by far. AND she had a surprising amount of agency for a female character in a film written by four middle-aged men in the early 1950s.

The Creature From the Black Lagoon was released in 3D, which again is impressive for the 50s. The technology was first implemented all the way back in 1922 and has been coming in and out of fashion ever since.

I can’t say I’ve ever seen it in 3D myself but I’m sure the effect was quite something to behold, especially in the cinema. I bet there were no 3D swamp men lurching at the camera in White Christmas.

Now, because the creature’s costume was heavy and dangerous when wet, the production had to hire a specialist to wear it. They chose Ricou Browning, a highly-trained under water stunt man. Whenever you see the creature swimming or submerged, he’s the guy in the suit. I read that he had to hold his breath for up to four minutes at a time during his scenes, and this was purely an aesthetic choice.

The director, Jack Arnold, thought that as the creature had gills it shouldn’t be seen expelling any air. That makes sense to me. Like I said, I love a good bit of logic. But If you actually watch the film you’ll see that the very first sign of the creature we see on screen is bubbles rising to the surface before a webbed hand rises from the murky deep.

I don’t often go full Comic Book Guy (which is a lie) but excuse me Jack Arnold – if indeed as you say the creature shouldn’t be expelling air, what, pray tell, was the source of those bubbles? Are we to believe the creature perhaps farted?

The bubble issue genuinely bothers me by the way. I appreciate consistency and continuity and more importantly I think it was mean of Jack Arnold to deny Ricou Browning all that oxygen. Worst director ever.

The costume was modified to include an air tank in the subsequent sequels. While obviously much safer, this had the unfortunate side effect that you can clearly see regular streams of bubbles bursting out through a hole in the top of the creature’s head. So, annoyingly Jack Arnold was kind of right. But that still doesn’t explain those bubbles at the 3:47 mark. They’ll haunt me forever.

This was just the first in a whole trilogy of films. Apparently Hollywood has always loved squeezing every last drop out of a franchise.

For the final two instalments the creature’s eyes were replaced with clear plastic bulbs to help the actors inside see what they were doing. I’ll admit he looked less scary in the next two, yes. But I applaud them for learning from their mistakes and trying to keep their actors safe.

Almost everything I’ve just told you has been ripped straight from the IMDB trivia page and there’s still loads more I want you to know. But why hear it from me? I’ve asked a couple of special guests to read you some more so here are Rory and Kit from This Paranormal Life with some juicy movie tid-bits.

Ricou Browning … once had to make an emergency bathroom visit while he was filming a scene. Browning had been underwater for several minutes and breached the water in full costume, next to an unsuspecting mother and her young daughter on the nearby shore. Browning said that they fled in terror once they saw him. He recalled, "they took off, and that's the last I saw of 'em!"

Can you imagine how terrified you’d be to be alone on the beach with your baby and a literal monster Hallie Berries out of the sea in front of you. Nightmare.

Jenny Clack of the University of Cambridge discovered a fossil amphibian, found in the remnants of what was once a fetid swamp, and named it Eucritta melanolimnetes - literally "the creature from the black lagoon".

This might be my favourite fact of all time. It was one of my Hinge prompts. I adore scientific names of animals and there are so many good ones that I’ll tell you about in the future but Eucritta melanolimnites could be the juiciest of them all.

When the Creature attacks Zee, the script called for him to pick him up and throw him into the camera for the 3-D effect. Unfortunately, the wires used to lift Zee up to make it appear as though he was actually being picked up by the Creature kept breaking. After two tries, Jack Arnold decided to just have Zee get strangled.

I love that one so much. Screw the mega-expensive 3D, just strangle him. We’re losing the light.

Thanks for that guys! If you keep listening you might hear from those two again later in the series.

I can thoroughly recommend reading the whole trivia page for yourself, there’s even more on there than Kit, Rory and I have already told you. In fact, I enjoyed it so much that I went straight on to the page for this film’s sequel Revenge of the Creature.

This is where the story really starts.

Revenge of the Creature was the most successful release of the trilogy. I think it’s fair to say that most of you won’t have seen it. And I don’t blame you. It doesn’t seem to be on any of the streaming services we’re all locked into these days. I had to buy it. With money.

Desperate times, guys. And if nothing else comes from me making this podcast other than these movies being put on Netflix it will have been a resounding success.

Unlike the first film, this one does not hold up in my opinion. They do bad science in Revenge of the Creature, and I take that personally.

Right at the start there’s a bunch of boring exposition, artlessly explaining how the creature could have existed all this time even though the science says it’s impossible. I’d love to have Rory and Kit read it to you but it was honestly too dull to transcribe.

Revenge of the Creature starts with a team of overtly sexist men in the black lagoon ready to hunt the monster down. They capture it almost immediately and manage to get it all the way from deepest Brazil to an oceanarium in Florida with very little effort.

It’s a normal marine park full of innocent unarmed civilians and pools full of fish, turtles and, of course, dolphins. The creature is unconscious when it first arrives, and so their solution is to place it in an open-air tank with no additional security.

Wouldn’t you know, he’s pretty angry when he wakes up and naturally begins to kick off. The park staff overpower him and chain him up in an empty tank, where the scientists attempt to train him... with a cattle prod. What could possibly go wrong?

I don’t want to ruin the plot for anyone who hasn’t seen it, but let’s just say that the monster puts up more of a fight than the dolphins do.

Interestingly this was Clint Eastwood’s first ever movie role. It’s a brief and bizarre cameo. He plays a lab assistant who tells his supervisor that one of the mice he’s studying has gone missing. He then finds the mouse in his pocket and is never seen again for the rest of the film.

The marine park they used in filming is real. It’s called Marineland Florida, and it’s a pretty interesting place in itself. Its original name was ‘Marine Studios’, and it was the one of the first oceanariums in history, if not the very first.

It was primarily designed as a place to capture footage of underwater animals. They planned to maximise their profits by charging studios to use it as a filming location and allowing the public to visit and pay an admittance fee of $1.

The concept was dreamed up by a trio of privileged young men in 1936. And I’m not just saying that. They were W. Douglas Burden, Cornelis Whitby and Ilia Tolstoy. As his name suggests, young Ilia was the grandson of world-famous War and Peace author Leo Tolstoy.

The other two of them were descendants of Cornelius Vandebilt who was one of the richest Americans in history. So I wasn’t exaggerating when I called them privileged. If anything, that’s an understatement.

Together they had the idea for a natural oceanarium. They initially envisioned essentially roping off a chunk of the sea. It would be separated by a submerged mesh fence made of strong steel. I’m not sure why but they soon changed their minds and opted for above-ground steel tanks totally separated from the sea but with big viewing windows.

Their biggest pool wound up 30 metres long, 12 metres across and 3.3 metres deep. If you’re American or British but over 65 and don’t know metres I can tell you in feet too. It’s 100 feet long, 40 feet in width and 11 feet deep.

News soon spread about the new attraction popping up and people were keen to see it for themselves. In fact when the facility first opened its doors on the 23rd June 1938 20,000 people flocked to buy tickets and caused an all-day traffic jam along the Florida coast.

But before the grand opening they needed to fill up their new tanks. After all, the people were coming to see the animals. So early in 1938 the facility’s specially designed capture vessel went out in search of prisoners. I mean, specimens. This boat was called ‘The Porpoise’ and could allegedly travel almost 1,000 miles without needing more fuel. Probable lies aside, The Porpoise did have a few special features.

The boat had a trapdoor at the rear, like a whaling ship, to make it easy to bring creatures on board. Animals were sedated and then stored in a flooded compartment below deck that was about six meters long and one metre across. That’s 18 by three feet. The captain of The Porpoise, Eugene Williams, proudly collected enough animals to fill one million gallons of water in the park’s tanks.

The Porpoise III can be seen at around the 17-minute mark in Revenge of the Creature. The very boat that was genuinely used to capture wild animals for the park was the one they used to bring the gill-man to the aquarium in the film. I don’t know if that’s irony or authenticity.

The studios were only used in five full-length movies between 1939 and 2001, and the park changed its name to Marineland Florida in 1961 when they couldn’t justify calling it a studio any more.

I don’t want to cast any aspersions but it seems to me like whoever was in charge of marketing this place wasn’t too talented. For around a decade the aquarium’s brochures focused entirely on the engineering of the facility and didn’t feature ANY pictures of the animals.

Marineland Florida still operates today on the very same site, although it’s completely unrecognisable from the location seen on screen.

But back in its heyday Marine Studios was selected as one of 20 locations for The Creature From the Black Lagoon. The whole thing was shot in Florida except a few little bits whipped up in Hollywood.

Fast forward a year, and the follow-up film ’Revenge of the Creature’ was being made almost exclusively at Marine studios. And one of its inhabitants was given a starring role. This was an animal billed as ‘Flippy the Educated Porpoise’.

Now I have to speak up here. We’re talking about a dolphin here, not a porpoise. I’ve seen the film hundreds of times. The animal in question is a bottlenose dolphin, I can tell you that with great certainty.

It would have been something pretty remarkable if they had managed to train a porpoise back in the 1930s. Porpoises are the smallest whales on Earth and are extremely difficult to train and care for.

They’re prey animals and they will swim away at full speed at any hint of danger. That flight instinct has been hard-wired over millions of years, it’s very difficult to shake. To this day there are only a handful in captivity.

So they didn’t educate a porpoise. A Chicago Tribune piece from 1951 described Flippy as

“A young male porpoise of the bottlenosed dolphin species.”

Now, that might not sound too odd to you. Porpoise, dolphin, what’s the difference? Those terms are pretty much interchangeable, right?

How dare you.

Porpoises are in a totally different family than dolphins. Dolphins are bigger, more intelligent and while there are a measly seven members of the porpoise family there are 42 different species of dolphin.

Don’t get me wrong, I love porpoises too. They just aren’t dolphins. Porpoises have flat teeth, dolphins have spiky ones. Dolphin dorsal fins curve backwards but porpoises have neat little triangle fins. For those seeking additional information about the differences between dolphins and porpoises please contact me directly, I have many more things to say on the matter.

And while we’re talking technicalities, Flippy wasn’t the only dolphin at the aquarium. Also on site - with an equally catchy name – was Moby the Educated Pilot Whale.

Pilot whales are dolphins even though they have whale in their name, just like how killer whales are dolphins too. Moby was captured from the wild, just like all the other animals at the park.

Oh, and both of the whales’ names the word educated is in quotes. Like, oh yeah they’re “educated”. Uh, excuse me! If I recall correctly you’re the ones doing the educating so who are you really hurting with those inverted commas? Apparently only me.

Flippy the “educated” porpoise the dolphin was the first of his kind to be put on permanent display and actually survive.

P.T. Barnum had tried and failed to display live whales and New York’s American Museum of Natural History had given it a go too. The museum put five dolphins on show to the public in 1913 but all five died before two years had passed. I’ll tell you what P.T. Barnum did in a minute, we’re not there yet.

Flippy was the one to buck the trend. At first the park’s presentations were simple feedings but visitors went nuts over it.

The whole concept of a marine park was brand new. People had never had the opportunity to see anything like this before and it became extremely popular. But soon the park operators wanted Flippy’s shows to be a little more entertaining.

They decided they needed to find an animal trainer to quite literally whip Flippy into shape. And who dared to take on this new and dangerous challenge?

The task went to a circus animal trainer named Adolf Frohn. He was the world’s very first dolphin trainer. Before working with Flippy his favourite animals to train were what he called seals. I’m guessing he meant sea lions. Seals are very sluggish on land, not particularly entertaining to watch at a circus. Very bitey too, as I understand.

But it seems that back then you could just call animals whatever you felt like. Anybody that wants to hear an exhaustive list of the differences between seals and sea lions my DMs are open.

Adolf Frohn was born in a circus wagon in Hamburg, Germany in 1904. He was a fourth-generation animal torturer – I mean trainer. He was working on a lion and tiger show with the greatest showman P. T. Barnum himself when he was drafted into service with Flippy.

I’m going to have to take a quick P. T. Barnum tangent now. I promised I’d fill you in. If you don’t have a clue who I’m talking about, Phineas Taylor Barnum was a businessman from the 1800s most famous for being the founder of Barnum and Bailey Circus.

Before that he had his own museum full of oddities from around the world, much like Ripley’s Believe it or Not but even worse. Sadly, many of his exhibits were living beings. He displayed both animals and people, though treated the latter a lot like the former.

He was the subject of the 2017 film The Greatest Showman. It was a dazzlingly colourful musical but if you ask me it brushed over quite a few aspects of the dark side of Barnum’s business. Since its release I think a lot of people seem to think Barnum was a cheeky little scamp with a heart of gold. I blame Hugh Jackman, he’s got almost too much appeal.

Now I can’t bring up a film without laying down some IMDB trivia. Let’s hear it, Rory and Kit.

Barnum's American Museum was so popular that the crowds inside would linger much too long, thereby cutting into profits. To make way for additional paying customers, he posted signs indicating "This Way to the Egress." Unaware that "Egress" was another word for "Exit," people followed the signs to what they assumed was a fascinating exhibit, and they ended up going outside.

Some might say that’s the mark of a good businessman. Others may consider that stunt to be a bit misleading. But if there’s one thing we can say about P. T. Barnum is that he was famous for his tendency to bend the truth. If you ask me it was more like he was twisting it up like a balloon animal.

During the filming of what would be the last take of the fire at the circus, the staged fire quickly became out of control when a large light fixture broke off the roof of the building and fell into the flames. Five retired volunteer firemen working as extras sprang into action to help keep the flames at bay until the FDNY could respond. Around 150 people were on set at the time, but because active filming had wrapped already, nobody was injured. The entire set was a loss, including $300,000 in lights. Though a huge loss financially and materially, the blaze gave the post-production crew a good idea of what the building would truly look like on fire, and provided the special effects team with valuable footage. The director kept the cameras rolling during the blaze.

What a fantastic example of life imitating art imitating life. Barnum’s museum really did burn down, although the occupants weren’t as lucky as the cast of the Greatest Showman.

Hugh Jackman read some three dozen books on P.T. Barnum to prepare for the title role.

I know that this was a real passion project for Hugh Jackman. He wrote the film as well as taking on the title role. I’m glad he did his homework, but a big part of me is disappointed that even with all that research he chose to make Barnum so gosh darn likable.

Because let me tell you, I don’t like P. T. Barnum. He wasn’t the loveable rogue Hugh Jackman portrayed him as. I think Voldemort would have been a better choice for that role. Not Ralph Fiennes, actual Voldemort. Here is a list of things P. T. Barnum genuinely did.

He caught wild elephants in Sri Lanka and transported them to his American museum in cramped conditions for four months without any fresh air. They did not all survive the journey.

Physically abused the animals, whacking them with a sharp bull-hook and burning them with hot pokers

Purchased an elderly African American woman named Joice Heth for $1,000 (technically he rented her as slavery was already illegal but Barnum found himself a loophole)

He made $1,500 off her a week and never paid her a penny. That’s a 50% return on investment every week.

He took her on tour, telling audiences she was more than 160 years old and had been George Washington’s nurse. She dutifully played her role, singing lullabies and telling stories about America’s first president that Barnum had made up himself.

When she died he charged people to see her body undergo an autopsy. The surgeon in charge determined she had only been 80 years old at the time of her death, at which point Barnum proclaimed that the only explanation was that Joice was still alive and the body being cut up on the slab must be somebody else.

If that’s not enough to sour the mood, the overt racism continues. Barnum put an African American man on display in his freak show under a poster reading -

For want of a positive name, the creature was called ‘WHAT IS IT?’

He literally named a human being ‘WHAT IS IT?’. It’s official. P. T. Barnum was a total scumbag that abused his ‘collection’ of people and animals.

On top of all of that Barnum’s enterprise had also done some trial and error with marine mammals. A pair of beluga whales

displayed at his Museum in 1861 died within two days of leaving the wild. Reports vary but nine or so more perished in the fire of 1865. But despite these horrendous failures Marine Studios decided Barnum’s guy Adolf Frohn was the right man for the job, for some reason.

He told the Chicago Tribune that at first, he didn’t think he could teach a ‘fish’ anything. Dude, dolphins aren’t fish. They’re mammals. But if I keep interrupting we’re never going to make it through the podcast.

You can probably tell from my tone that I kind of hate Adolf Frohn. And at first so did Flippy. It took him three months to stop freaking out every time Adolf showed up.

That’s pretty typical even now. A lot of dolphins in captivity to this day have been taken from the wild and have difficulty adjusting to their new, and very different surroundings.

Eventually the dolphin started tolerating his new trainer’s presence. Despite being a huge genius and having years of experience training animals that lived in water, Adolf couldn’t swim.

He delivered his instructions to Flippy from a rowing boat. He barked his commands and if the dolphin did what he wanted, he offered him a fish. Adolf wrote extensively about his frustration with Flippy whenever he got distracted or if he forgot something he’d been taught the previous day.

He also complained about how Flippy would go through periods of lethargy and ill temper. That really got on Adolf’s nerves. He told colleagues he’d prefer to train a female dolphin next because he thought they might learn more readily, even though - according to him - they’d probably need more affection than a male. Ugh, this guy.

Another thing Adolf lamented was Flippy’s tendency to get ‘stuck’ learning a trick. Adolf would give him a command but hadn’t yet taught him a signal that meant ‘stop’. So Flippy would throw his best tricks over and over until he was too exhausted to continue. And Adolf blamed Flippy for that.

So far it had been a struggle but he reported a breakthrough moment in their relationship when one morning, Flippy leapt clean out of the water and into Adolf’s arms, almost splintering the hull of the flimsy boat. It’s interesting to me that he interpreted this as a show of affection rather than an attempt on his life. If it ever happened at all.

The account of the incident I found painted Mr. Frohn quite favourably, and stated that he heroically (and gently) returned the (200 lb) dolphin to the water and made it back to dry land before his boat sank like Pirate of the Caribbean Captain Jack Sparrow himself. And everyone clapped.

Nonetheless, the training continued. Flippy learned to catch a football in his mouth, honk a horn and drag along a surfboard ridden by a woman and a fox terrier.

Flippy’s education went on for three long years. The endeavour cost around $1,000 a month, and in today’s money that amounts to over $670,000 to train one dolphin.

So, this expensive enterprise needed to pay off big time. And how better to get Flippy’s name up in lights than to give him a name check in a Hollywood blockbuster. And that brings us back to the creature from the black lagoon.

Flippy appears as himself in Revenge of the Creature. His show takes up an entire scene. He does a few tricks. He jumps up and rings a bell, fetches a toy and for the grand finale leaps out of the water raises a flag.

The crowd clap, cheer and laugh and the characters talk at length about how smart “porpoises” are. Oh, the irony. But Flippy the Educated porpoise’s handful of basic tricks were a hit. That was three years well spent for Adolf, clearly.

Okay, I know I’ve been pretty harsh to Adolf here. I know he wasn’t - y’know - evil.

I just have very strong feelings about dolphins being in captivity. But I know if it hadn’t been him, it would have been someone else. He grew up 100 years ago. They didn’t know any better back then. That’s just how things were.

But I still think I’m allowed to be angry. Injustice is injustice. Animals have been treated terribly throughout the course of history. Like the belugas that P.T. Barnum boiled to death. That’s an awful thing that shouldn’t have happened. It’s good that things are better now, but as you’ll hear throughout this series they still aren’t great. And Adolf’s a great lightning rod for all my dolphin-fuelled rage. Especially because when asked by a journalist in 1952 if Flippy might be smart enough to talk one day he replied –

He already is, we’re just not smart enough to understand him.

Okay, what does that mean? Did he really think that or was he just trying to be deep and poetic? If so, mission accomplished. The line had such an impact on the writers of Revenge of the Creature it made it into the script three years after Adolf first uttered it.

I concede that there’s no way he could have known how intelligent this dolphin was. That’s something we can’t be sure about today, we still don’t have the answers after decades of research.

But if he truly meant what he said before it’s a bit sad he didn’t take the chance to really think about that and consider whether or not he was doing the right thing.

That Chicago Tribune piece I referenced earlier ended with the following sentence.

Flippy’s built-in grin seems to indicate that he derives enjoyment from being the world’s most educated porpoise.

That was written by Bob Neelands in 1951. Well, Bob Neelands, you’re an idiot. You’ve missed the point, mate. You said it yourself, that grin is built in. It doesn’t indicate anything.

That’s literally just the shape of their mouths. They have resting angel face. Don’t let that smile fool you into thinking they’re happy. It means they’re dolphins, that’s it.

But there’s even more to Flippy’s story. Remember the stunt man from Creature from the Black Lagoon, Ricou Browning? The man behind the fishy mask.

He wasn’t the director’s first choice for Revenge of the Creature, although I’m not sure why. Maybe the two fell out over the oxygen deprivation issue. He was uniquely qualified for the role. Before participating in the first film he’d spent years doing stunts under water on camera for TV ads and other projects. But by the time he even heard about the sequel they’d already started shooting.

Director Jack Arnold called him up out of the blue and asked him to get himself to Marine Studios as soon as possible. It turned out the replacement he’d chosen to play the gill man had lied on his CV and couldn’t actually swim. He had experience as an underwater camera operator but couldn’t handle any of the actual stunts.

The production had cast him his very own extremely pricy made-to-measure monster suit that they had to quickly cut down to fit Ricou Browning. Within three days of that phone call the production was back in business and there was no question about hiring Ricou Browning for the final film of the trilogy.

If anyone’s interested, the third and final installment was called The Creature Walks Among Us. I’m about to spoil the entire plot so skip ahead 30 seconds if it’s somehow on your watchlist. In a nutshell they catch the creature again but this time around he gets burned in a fire.

They give him surgery and he starts shedding his monster skin, which makes him look human. Then they make him live in civilised society but all he does is look at the sea all forlorn and stuff.

Then some jerkwad with serious sex offender vibes gets murdered by another character and – though innocent – the gill man gets the blame. He ends up having to kill his way out of the whole situation and the last time we ever see him he’s walking back into the ocean where he belongs.

That wasn’t the last time the gill man appeared on the big screen though. And no, I’m not talking about Creature From the Black Lagoon: The Musical. Because that was briefly a thing.

It was a live show at Universal Studios Hollywood that replaced Fear Factor LIVE. You know these performances they put on throughout the day to give the squares that don’t like rides something to do while all of us rad people are out living life.

I actually saw Fear Factor LIVE and in all fairness it was brilliant. A guy brought out this big box and said that it contained the world’s largest spider. When he opened the box it was rigged so that this massive toy spider launched out into the audience then played back the front row’s reactions on the big screen. The woman shielded herself from the tarantula with her own baby. Classic.

But in 2009 they’d probably received enough complaints about spider trauma to switch things up. The Creature from the Black Lagoon: The Musical was 25 minutes long and according to its Wikipedia page it was ‘loosely based on the basic plot’ of the 1954 film.

The premise boiled down to the idea that the original movie was based on true events and the audience were about to watch the exploration team go and catch the real creature. And also, singing!

It might sound rubbish, and in all honesty it wasn’t well received. It only showed for five months all told. In March the following year it was replaced by an attraction called Special Effects Stage, which like Fear Factor LIVE I have also seen. I can't believe I missed Creature from the Black Lagoon: The Musical, which I will hereby refer to as the Blagoosical to save us all some time.

Thankfully I’ve seen it now that I’ve found it on Youtube. It has four original songs, two of which are performed twice. I think my favourite part hands down was the disclaimer they played at the beginning. The light dimmed and the music stopped as the announcer said -

Ladies and gentlemen, the show you are about to experience depicts an unnatural romance. This relationship is performed by two highly trained professionals and so we ask that you don't attempt to engage in an unnatural romance and home and remind you that even your average garden variety romance involves a frightening degree of risk. Thank you.

Hilarious, right? Got nothing from the audience in the YouTube video.

The Blagoosical was tongue-in-cheek and laden with innuendo. It centred on Kay, the female lead. She sings wistfully about finding 'a creature who will slay me'.

Like in the OG film, she gets kidnapped by the gill man but twist! She quickly develops affection for him and is very outspoken about it. It would have been more shocking if I hadn't seen Beauty and the Beast as a child but here we are.

It's a wild ride from start to finish, pop it on if you've got a spare half an hour. There are crazy aerial swimming stunts, a tap-dancing gill-man and I did not see that surprise ending coming. I honestly considered not telling you how it ends because it’s that good but it's worth seeing even if you already know what happens.

They accidentally shoot the monster with a tranq dart full of growth hormone and then he appears as a massive animatronic head and shoulders. No knees and toes. Kay chooses to leave the other humans behind to go to him. He lifts her up, pulls her close and … swallows her whole.

Such a good twist. They say the creature animatronic is still on the same stage today, just hidden behind the set for the current show. I’m begging you, if there’s anybody listening that can confirm that I’ll be the happiest person on Earth.

I would have loved to see the Blagoosical with my own eyes. Maybe one of the lucky few hundred people that did bear witness to it could have been mega-famous filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro.

I concede that it’s unlikely, but I know for sure that The Creature from the Black Lagoon was hugely inspirational to Guillermo Del Toro when making the Shape of Water, the most recent effort to bring the gillman to a cinema near you.

If you haven’t seen it I can give you a quick outline. Prepare for spoilers. Also prepare for some hot takes on quite a lot of people’s favourite movie.

Some government agency captures an aquatic humanoid monster and lock him in a secret facility where a kind deaf cleaning lady takes pity on him. They fall in love and she busts him out to set him free. There are a few hiccups but in the end they escape and can start a new life together.

I read that Del Toro wanted to toy with the idea of the run-of-the-mill monster kidnaps screaming woman trope. I must say I thoroughly appreciate the consent of it all.

I don’t, however, appreciate how UNREALISTIC so many parts of it are. That was my problem with Revenge of the Creature. People don’t behave like that in real life. I hope I’m not upsetting huge fans of the film but I have serious points to raise here.

Why do the cleaning staff have seemingly unlimited unsupervised access to a top-secret specimen? Surely his every move would be monitored and his diet would be closely controlled, nobody would be allowed to feed him eggs willy nilly. That wouldn’t fly in a commercial aquarium, let alone a state-of-the-art government facility.

Although thinking about it now, it’s probably because the men at the top see the women as insignificant. They don’t monitor them because they have no regard for them and don’t expect them to be capable of anything besides cooking, cleaning and speaking when spoken to.

Another thing that gets to me that will make no sense if you haven’t seen the Shape of Water is - Why does the old man keep buying pie he doesn’t like? I understand wanting an excuse to talk to cute guys, but buying a dessert you don’t want every day of my life is the definition of lunacy.

I mean, I suppose if the cute guy had recommended the key lime on my first visit I might have pretended to like it. And then when you go back you might feel pressure to order it again. But there were plenty of other dessert options on clear display in the Shape of Water, why not try one you might actually enjoy?

What about this one? In what universe is that ramshackle old bathroom watertight to that degree? Those are bare wooden floorboards, that thing’s essentially a sieve.

Yes, some water drips through to the cinema downstairs but not enough to be plausible in my book! AND in the end why does the Russian spy guy give up where the women are releasing the creature literal SECONDS before he dies? So unnecessary! He could have so easily taken that secret to the grave.

This one’s probably down to my own stupidity but I wasn’t sure what was going on in the end. Was the Mum from Paddington also a creature from the black lagoon all along? Did he turn her into one? Was it somehow both … or neither?

If you haven’t seen the Shape of Water that probably meant nothing to you so sorry about that. It wasn’t relevant to the subject of the podcast so you haven’t missed anything important.

In both movie universes the creature manages to escape captivity in the end, unlike Flippy or any of the other animals you see in Revenge of the Creature. In fact, Flippy passed away the same year the film was released after 17 years in captivity. He was replaced by another bottlenose named Flippy 2. I’m simply staggered by their creativity.

But back in 1955 the OG Flippy’s talent caught Ricou Browning’s attention. During his time shooting at Marine studios he watched this dolphin play around and do his tricks and a lightbulb lit up in his head

He remembered the look of rapture on his children's faces when they watched the TV show Lassie. You know, that TV show about the dog that rescues little Timmy from down various wells?

Browning was so inspired by Flippy’s charm and playful nature that he decided to pitch a movie about a friendly dolphin that helps out humans in sticky situations. You might have heard of it. Flipper? Flipper the dolphin?

The magic of meeting this one single dolphin was impactful enough to generate a highly lucrative franchise that spanned more than 50 years.

Perhaps an unintended consequence of this idea was bringing dolphin-mania to America, and eventually the world. But that’s a story for next time.

Episode 2 – On the Origin of Dolphins

Welcome to A Dolphin Pod. I’m Amy Grisdale. I’m a stand-up comedian, marine biologist and writer for This Paranormal Life because everyone born in the 90s has at least three jobs.

This is episode two. If you haven’t heard the first episode you might miss some of the references in this so it might be an idea to hop back and catch up. But we aren’t picking up that story today.

Before we continue with that I think it’s time we learn all about dolphins. Well, there’s still a lot we don’t know. But there’s a ton of stuff we’ve got set in scientific stone.

For one thing, we know exactly how they evolved. I don’t want to worry anyone but it’s a long story that starts 55 million years ago. It’s probably best if we just jump in and start getting through it because I have a lot to say. Pens at the ready if you’re planning on taking notes.

The dinosaurs have already been and gone. They’ve been extinct for 10 million years. Mammals have taken over the land. The land, that is. Not the sea.

As far as we know the earliest mammals to evolve were shrew-like little beasties that ate insects and laid eggs like the duck-billed platypus. But as time went on there was an explosion of diversity and new species were popping up left, right and centre.

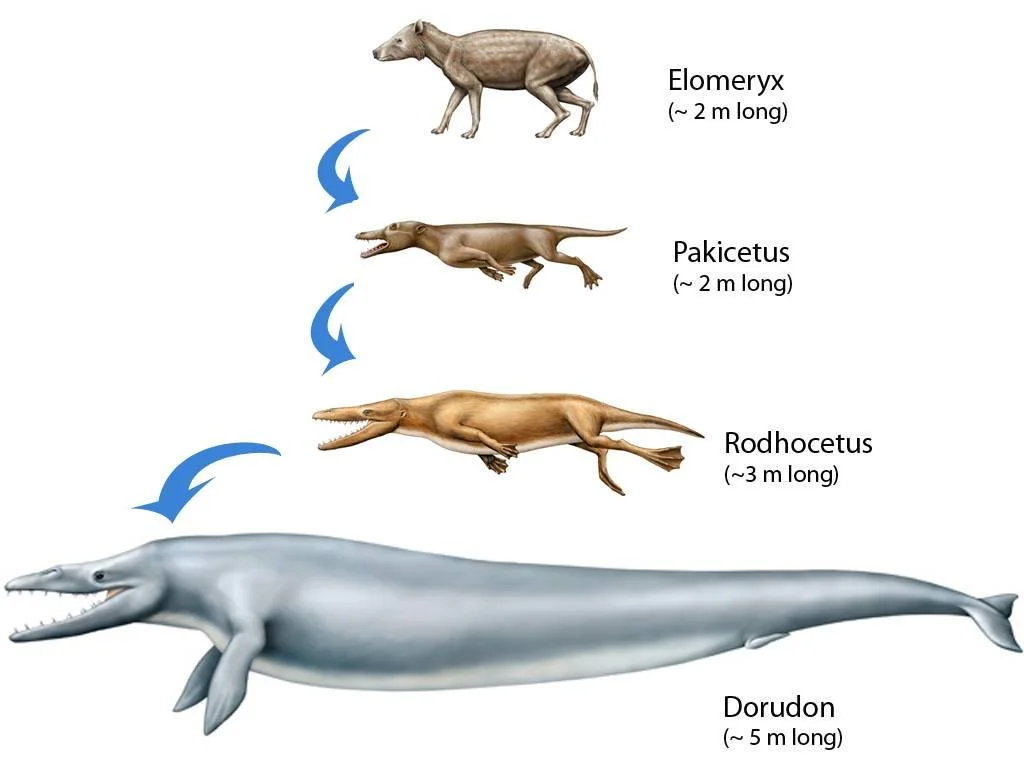

Most of the animals that lived in this period are long extinct now but during their time on Earth they made choices that impacted the wildlife of today. My favourite example of what I’m talking about is a little mammal called elomeryx.

Imagine a furry little hippo with long, skinny legs and you’re close to picturing elomeryx. It’s a herbivore and has teeth specialised to shred water plants. It lived a happy little existence but couldn’t help but notice the land was getting a bit crowded. Meanwhile, the ocean was teeming with food and nothing was taking advantage of it.

Wanting to avoid having to compete for resources, elomeryx started venturing further and further into the water to find food. Over a ridiculous amount of time they moved into the water on a permanent basis. Every part of their body changed to adapt to their new environment.

Firstly, they lost all of their hair. They didn’t need it to keep warm any more, and without it they were more streamlined in the water. The nostrils travelled from the front of the face to the back of the head. This made it a whole lot easier to breathe while swimming.

So that blowhole we see on a modern dolphin’s head is basically the animal’s nose. If you look down it you’ll see there are two chambers inside, like a pair of nostrils.

Another huge change the animals underwent was the shrinking of their back legs. Within around 15 million years the hind limbs were gone and had been replaced by a superior form of transport. The powerful tail flukes replaced the outdated four-legged doggy paddle.

But the back legs didn’t disappear entirely. If you ever see a skeleton of a whale, dolphin or porpoise you’ll see two sets of tiny leg bones on either side of the pelvis. The tiny leg remains are embedded under the blubber and are our biggest piece of evidence that whales once walked on land. Otherwise why would they be there?

Now I’m sure some of you are wondering – how though? How does that happen? What causes an animal to go bald, lose limbs, sprout a tail and even have a natural nose job? I’m glad you asked.

Bear in mind that this process spanned more than 50 million years. That figure is difficult to process for us humans. We think a microwave minute is a long time. Not one of us knows what it’s like to experience much more than a century on Earth.

But the planet has been here for almost five billion years, and that time has had a staggering effect on the animals that surround us today. When elomeryx and its prehistoric pals were first dipping their toes into the water, some are bound to have been naturally more suited to ocean life. Maybe a few had larger-than-average front paws that made swimming easier.

One or two might have had nostrils that were slightly higher up the snout than the rest of the species.

It’s possible that some had waggy tails that liked to do overtime. Every member of a species is unique, and their tiny variations mean the difference between life and death. It’s survival of the fittest. Natural selection. Whatever you want to call it.

Over time these differences can work in the animal’s favour. For example, a swimming mammal born – by chance - with its nose higher up on its face could be less likely to drown. Those are the animals that survive long enough to reproduce and pass on their DNA. That means their babies also have swimming-adapted nostrils too.

The animals that struggle to keep their nostrils above water don’t last long. Maybe not even long enough to breed. As a result, their genes don’t get passed down to the next generation and the species starts heading in a new direction.

The genes that help a mammal survive at sea are passed like a torch from adult to baby. Weak genetic material either means an animal doesn’t live into adulthood, or isn’t chosen as a mate by a member of the opposite sex. It sounds immensely unfair, but nature is brutal.

Only those that can adapt can survive. Eventually these ancient animals diverged into around 90 varieties of whale, including 40 different species of dolphin alive today, depending on who you ask. They all look and behave slightly differently but share a lot of traits. They’re all smart and powerful predators thanks to all those million years of evolution, but the similarities go far deeper than that.

Dolphin skeletons are extremely similar across the board. If you were to take an x-ray of a dolphin’s pectoral fin – those are the flippers on each side – you’ll see that they contain five long fingers. The exact same bones we have in our hands.

There are no bones in the tail however. It’s made of cartilage, just like our ears are. It’s the same with the dorsal fin. That’s the fin on a dolphin’s back, although there are a few species that don’t have a dorsal fin at all. If you want to know which ones, get in touch.

Woah guys! If you’re that desperate head to adolphinpod.com, I’ve already written a blog post about dorsal-less whales just for you.

So anyway, if you look closely at the sides of a dolphin’s head you’ll see two tiny openings. These are all that remain of the external ear flaps their land-lubbing ancestors once had. Dolphin eyes also have some cool features. They move independently so they can look in two directions at once and are far enough apart to give the animal 360 degree vision. They produce a sticky mucus called ‘dolphin tears’.

This stops the eye from getting scratched when the dolphin’s swimming at top speed. It’s thick enough to come away from the eye in a single sheet and yes I agree, it’s disgusting.

Dolphins can see and hear perfectly both above and below the water. That’s one of the things that makes them such good predators.

Despite the similarities in anatomy there’s a lot of variation across all the different dolphin species. Some live in fresh water, others hug the shore while many prefer the deep open ocean.

This might also be a good time to clarify that all dolphins are whales. That’s right, it’s technicality o’clock. Generally speaking there are two types of whale. You’ve got your big filter feeders like the blue whale.

The science word for this type of whale is mysticete. Then there are toothed whales AKA odontocetes. Toothed whales include belugas, narwhals, porpoises, beaked whales and all the little weirdos in between. And dolphins, of course.

In general dolphins aren’t too fussy about what they eat as long as there’s plenty of it. With an insane daily demand for almost 50,000 calories, it’s vital that they work out strategies to get a lot of food in a short time, with as little effort as possible.

Obviously, they can’t click and collect. They have to find their own food in the vast ocean. One thing that helps a dolphin do that is echolocation.

If you’re unsure what echolocation is I’d better explain. Dolphins use sound to see. They project out noise and listen for the returning echo. It’s just like how we use our eyes. Imagine you’re in a dark room and you’ve dropped your keys.

Let me bring it to life for you.

*LIGHT SWITCH SFX*

*KEY DROP SFX*

Oh dear, I seem to have dropped my keys. I think what I’ll do is take out my phone and turn on the torch. The beams of light are shining out and bouncing around the room, then back into my eyes, allowing me to see. Now I’ll just sweep the torch back and forth along the floor until - ah! There they are!

*KEY PICK UP SFX*

Dolphins do exactly the same, but they use beams of sound instead of light. Hold on, I don’t want to do the rest of this in the dark.

*LIGHT SWITCH SFX*

All the noises they make come from the blowhole, not the mouth. Dolphins don’t have vocal chords. Common misconception. Their vocalisations are generated by structures called the phonic lips hidden inside the blowhole. The phonic lips smack together and generate clicking sounds.

They come out as a rapid sequence that sounds like buzzing to our ears. The sound travels out into the sea ahead through the melon, a clump of fat in a dolphin’s forehead. This focuses the clicks into a beam that the dolphin can control.

You know those torches where you can change the width of the beam? You can do a really bright narrow beam like a laser pointer or a spread-out low-light affair to set a spooky mood on a camping trip?

Dolphins and their relatives scan the landscape in ‘wide mode’ but hone in and focus the sound on a single fish. It’s incredible.

So once the sound has been sent out, it bounces off any solid objects in the sea ahead. The echoes travel back to the dolphin and are picked up by the lower jaw. The sound travels along the jaw bone and into the inner ear, allowing the animal to build up a mental picture of its surroundings.

And that beam of sound allows a dolphin to A) See in darkness, murky water or if the dolphin’s eyesight is damaged and B) to see through objects like a living x-ray machine.

I know that aquariums that offer dolphin swims don’t like pregnant women participating because dolphins can see into the womb and have been known to get a bit – rammy – with them.

You’ve been warned.

But a dolphin can swim along the sea bed, echolocating away, and detect animals buried deep under the sand completely invisible to them. Then they go in with the teeth.

Everything a grown dolphin eats is swallowed alive and whole. The strong stomach acid reduces the entirety of the meal into a fine powder that exits the body in a delicate greeny-yellow plume.

I warned you this was ALL about dolphins, didn’t I?

They don’t use their teeth to chew, more to grab and hold a fish in place before it goes down the hatch. Interestingly, most mammals have a variety of types of teeth. We’ve got molars, canines and incisors and they all have different functions.

Not dolphins though. Their 70-100 teeth are all the exact same shape and size, a trait more commonly found in reptiles than mammals. The scientific term for it is homodont dentition. Homo meaning same, dont meaning tooth.

These teeth have another function besides pinning down wriggling fish. They scratch one another with their teeth, leaving parallel lines we call rake marks. Most toothed whales do it. Some species, like Risso’s dolphins, scratch one another so intensely that over time their skin forms permanent scars and turns white.

The wounds bottlenoses inflict on each other can be quite deep, but like I mentioned earlier, dolphin skin heals extremely fast. Raking is an expression of aggression, and it’s most common between rival males.

Dolphins communicate with others constantly, and it’s not just with their teeth.

They make a variety of different sounds from buzzes and clicks to musical whistles. We have been trying to decode dolphin language for decades and have made basically no progress.

It’s unbelievably complex and we might never know exactly what they’re saying to each other. Remember we’re talking about a species separated from us by tens of millions of years of evolution. What are the chances they communicate remotely similarly to us?

We might never fully understand dolphins. We might not discover exactly how intelligent they are, how they perceive their environment or how they feel about their friends. We’re on the same planet, but living in different mediums makes the dolphin world seem very alien to us.

Another important point, dolphins are what’s known as conscious breathers.

Every breath is a choice. We can go into autopilot with our respiration, otherwise we’d all die in our sleep. The thing is, a dolphin would die in its sleep if it took a breath underwater.

You know it would only take a single tablespoon of water getting in a dolphin’s lungs for it to drown. It would take double the amount to kill a human. They’ve evolved to live at sea but us solid groundies are somehow twice as hard to drown. That’s insane to me.

But that’s the weird cost of being a mammal in the sea. To get around the problem dolphins don’t really sleep in the traditional sense. They rest one eye and one half of their brain at a time. It’s called unihemispheric sleep. This way they’re alert enough to come to the surface to breathe around the clock. A dolphin is in total control over when their blowhole opens.

They don’t need much sleep. Bottlenose dolphins can go 15 days straight without rest. We can’t do that. Well, technically we can. There was a sleep deprivation study in 1964 in which a 17-year-old man named Randy Gardner stayed awake for 11 days and 25 minutes.

By the end of the experiment he was still in okay physical health and he was still mentally alert to play pinball but he was moody, paranoid and had started hallucinating. Nobody has ever broken his record. Please don’t take that as a challenge.

Something really astonishing is that dolphin memory is basically as good as human memory. Captive animals have been documented to remember tank-mates they haven’t seen for more than 20 years.

And at this point I’d like to make it clear that not all captive dolphins were not born in captivity, but were taken from the sea. That might have been okay in the eyes of Adolf Frohn but I think most people would agree that at the very least that seems harsh.

These days many are bred in captivity, but for a long time, most were taken from the wild. Many still are, and those that spent time in the wild will remember their former life before being made to take centre stage. I don’t want to make this a sad episode, I just needed you all to know that before I carry on.

Bonds between mother dolphins and their calves are incredibly strong. Orca calves, the largest of all dolphin babies, can spend their entire lives swimming alongside their siblings, mother and even grandmother. And some of us struggle to get through Christmas dinner.

Dolphins of all species are inseparable from their calves and develop an unbreakable bond.

It starts from birth. Mothers don’t sleep for two months after giving birth, babies do. The calf coasts alongside its mother in a slip stream she creates. Of course, the baby dolphin needs to be fed. And like all other mammals, newborn calves feed on their mother’s milk. There’s a long, thin opening on the underside of a female dolphin. This is the genital slit.

I don’t have to spell out what’s in there, but either side of it are two inch-long slits. These contain the mammary glands. When a calf takes a drink it curls its tongue up into a straw and inserts it into the mother’s mammary slit. That forms a tight seal and prevents the baby from getting a mouthful of seawater.

After two years young dolphins start to eat solid food like their parents. Ah, they grow up so fast.

And speaking of grown up, that brings me on to some of the spicier stuff dolphins do. It’s not just coral that dolphins use to self-medicate. At least, we think. It’s yet to be 100% confirmed because it’s only been seen happening a handful of times.

Back in 2013 the BBC were gathering footage for a documentary called Dolphin: Spy in the Pod. They spotted a group of dolphins taking turns to gnaw on a pufferfish. These inflatable fish are full of toxic venom that could kill a human almost instantly, but it doesn’t affect dolphins in the same way.

We don’t know exactly how it makes them feel but Rob Pilley, the producer of Spy in the Pod, described it like this:

This was a case of young dolphins purposely experimenting with something we know to be intoxicating ... After chewing the puffer gently and passing it round, they began acting most peculiarly, hanging around with their noses at the surface as if fascinated by their own reflection.

Interesting, I’m sure you agree. Again, we can’t be certain what’s going on but I’m getting real puff, puff pass vibes. There are other things that dolphins do that would seem questionable to the average person. For example, some dolphins at least appear to hunt for sport.

Here’s an example. In 1997 a pod of dead porpoises washed up on a few different beaches on each side of the Atlantic Ocean. The carcasses were examined by scientists and it was found that they were covered in bruises and had suffered broken ribs, ruptured organs and punctured lungs.

The final nail in the coffin was that they were covered in rake marks, which are the scratches dolphins leave with their teeth. It was concluded that the porpoises had been beaten to death by bottlenose dolphins, and slowly too. There’s not much in the way of a rationalisation for this besides the idea that the dolphins did it for fun. Yikes.

This is also the kind of thing orcas do. It’s brutal, but we think they do it to help their babies learn to hunt. Maybe bottlenoses do it for the same reason. I can’t pretend to like it but like I’ve said before, nature is absolutely brutal.

There’s more. Dolphins have been known to kill their own kind. It gets worse. Adult males target young calves in order to make their mothers available again. It sounds awful, because it is.

However, in their defence they are far from the only animals to do that kind of thing. When a new male takes over a pride of lions he kills the cubs so that the females will come into oestrus and all the next babies will be his.

One thing I hear people say a lot is that - trigger warning - dolphins are capable of rape. I can’t say I like using that word in any context, but especially when it comes to animal behaviour.

Here’s an example. You know hares? They’re like rabbits but bigger and less cuddly. When a female hare is ready to mate, she takes off running. A group of males chase her and she runs until she’s physically exhausted.

Once she gets so tired that she can’t take another step, the first male to reach her is the one that gets to mate with her as she lies on the ground catching her breath.

Now, if you heard about that happening to a human woman you’d be outraged. And quite rightly. The thing is, that’s how hares do it. The female is giving the males a chance to prove their genes are superior and only the fastest one is allowed to father her future offspring.

Humans do the same thing in a different way. We prove our value to others by dressing up nice, telling hilarious jokes and making entertaining but scientifically accurate podcasts.

We can’t help but see the animal kingdom through our own human-shaped lens. What we could call assault, a hare would call a standard, run-of the mill sexual encounter.

When it comes to dolphins there are lots of reports of sexual behaviour towards humans in captivity. We can squarely lie the blame for that at the feet of the people that put the dolphins in captivity in the first place.

There are some that say even wild dolphins will attack humans for their own gratification. I’ve spent way too much of my life looking for examples and I’ve read a lot of stories (that have absolutely zero evidence) and a couple of hoax scientific journals that gave me a good laugh.

I watched a few videos that show what I would describe as more playful behaviour than sexual aggression. But again, we’re humans and we have our own rules. We need consent and there are moral and legal consequences for not seeking it.

A dolphin can’t ask a human if they’re down to clown. We don’t even know how they communicate with each other when it comes to intercourse.

There’s a specific term scientists use. ‘Aggressive herding’ is the act of a group of male dolphins isolating a female from the rest of her pod.

They’ll pursue her and swim right up close. Sometimes they’ll slap her with their fins or push up against her with their bodies. They even rake her with their teeth.

Soon they begin to leap, bellyflop and somersault around the female, almost like they’re in some kind of dance-off. They take breaks to chase her if she tries to escape before they’ve mated with her.

Again, if we were talking about humans I’d have just described a horrifying and totally bizarre sex crime. But we don’t know if, like hares, the females are taking the opportunity to assess which males are worthy to be fathers. We can’t call it rape because that’s a human concept.

Something you might think is totally unique to humans is culture. Culture’s a weird thing that I personally don’t truly understand because I’m a white person and we don’t really have any. So, let’s clear up the definition of culture right now.

Basically, culture is

the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society

Ah, so in the UK we have a culture of binge drinking and not-so-casual racism. I wish I was kidding. But we feel the differences between different global cultures. Visiting a distant country feels different from home. Believe it or not, dolphins experience that too.

There are countless hunting strategies that the 40-ish dolphin varieties have devised, and you might have seen the incredible footage of small groups of dolphins within the same species working out unique hunting techniques in recent documentaries.

For instance, bottlenoses in the estuaries of Georgia and South Carolina have learnt to drive fish towards the muddy banks of the river. With nowhere to swim or hide, the fish flop on to the shore. The dolphins launch themselves up the verges and snap up the flailing fish before wriggling back into the river.

They always beach themselves on the same side of their body because picking up fish from the thick, silty mud erodes their teeth. Consistently wearing down only one side leaves the other half intact and ready to use.

Dolphins don’t chew their food. Their teeth are just there to hold the animal in place if it’s struggling to get away and they can accomplish that with half a set. As far as we know these are the only dolphins in the world that have figured that whole thing out.

Meanwhile on the other side of the world, Australian bottlenoses use sponges to forage in rocky areas to protect their beaks. They’re using tools to hunt. Not just that though! Dolphins that use sponges are more likely to hang out with other sponge-users.

They’re choosing to spend time with others with similar interests. Let that sink in. This is culture in a non-human animal. They’re making traditions that are handed down through generations of animals.

Indo-pacific bottlenoses rub themselves with coral for its medicinal properties. They know exactly which species to target. When they interact with it it produces mucus that helps regulate the microbiome of their skin and stave off infection.

Dolphins even develop regional accents, so a bottlenose off the coast of Australia sounds totally different to, say, a dolphin that lives in the pacific northwest … to other dolphins, at least.

The thing about these animals that really enraptures us is their intelligence. Flippy was considered to be ‘educated’ because he could jump out of the water and ring a bell.

That might have been groundbreaking in 1938, but Adolf Frohn’s tiny mind would be blown by what we’ve discovered since then.

We now know that dolphins have an extremely high EQ. And I do mean EQ, not IQ. It stands for encephilisation quotient (check me out) and that is a measure of the relationship between the size of an animal’s brain and its body.

For example, a Tyrannosaurus rex brain was much larger than a human’s if compared side by side, but it was pretty small in comparison to its huge body size. Human brains are at the top of the EQ scale. That means we have the biggest brains on the planet in proportion to how big the rest of us is. Dolphins are second on that list.

We also know that they are self-aware. So much so, that they can recognise themselves in a mirror. And that’s something we can prove. A 2001 study by Dr Lori Marino and her partner Dr Diana Reiss demonstrated beyond all reasonable doubt that dolphins know that they are the animal in the mirror.

The experiment took place at the New York aquarium. The researchers plunged mirrors into the water and observed what the dolphins did in response.

At first they showed aggressive or playful reactions, as if they were under the impression that they were looking at another dolphin.

Soon they began to show exploratory behaviour towards the mirror. The dolphins would look behind the plane of glass to find their new friend, and soon the penny dropped.

The dolphins soon started to test the mirror. They contorted into bizarre shapes, snapped their jaws and blew plumes of bubbles from the blowhole all while gazing at the reflection.

Just like a toddler dancing and pulling funny faces at its own image. This stage demonstrates that the dolphin understands that the movements it makes are copied in the mirror. But the research team took it one step further to get conclusive proof.

They took some markers, and drew shapes on the animals bodies. If you think that’s cruel, don’t worry. They used skin-safe ink and dolphins shed skin cells insanely fast so the marks were far from permanent.

Dolphin skin is really flaky so it peels away easily to reduce drag while swimming and wounds heal quickly. In fact, bottlenose dolphins can shed an entire layer of skin in just two hours.

But back to the experiment. Some of these markers were filled with water instead of ink as a control, to prove that the act of marking the animal didn’t have an effect on the outcome.

After being doodled on by the scientists, the dolphins were allowed to visit the mirror.

Those marked with the inkless pens had a quick look and saw there was no mark. They just swam away from the mirror to do their own thing. However, those with ink on the skin spent a significant amount of time looking in the mirror.

Wherever the blemish was on the animal’s body, it would orient itself so it was visible in the mirror. If the spot was on the animal’s back it would crane its neck to catch a glimpse of its reflection. If it was on the chin, the dolphin would raise its head to expose the ink mark.

This wasn’t a one-off study, and the researchers continue to examine how young dolphins develop their self-awareness as they mature. As it turns out, growing dolphins experience the same developmental stages as human children and at roughly the same age.

While your two-year-old is gleefully waving its arms to make its reflection move, the baby dolphins Dianna Reiss studies at Baltimore Aquarium are watching themselves doing backflips and crafting bubble rings.

In fact, dolphins can get the knack of this in just six months. It takes human babies around a year and a half.

While humans are undoubtedly the best thinkers on land, there may be areas in which dolphins might outsmart us.

Their communication could be more efficient than ours. Think about it. Our primary sense is our vision. We take in the world through our eyes.

However, our dominant method of communication is through sound. If I want to tell you about a tree I saw earlier, I could describe it as a tall sycamore with green leaves and a brown trunk. I’m a dazzling conversationalist, I know.

You might be able to imagine the tree I’ve described, but the picture in your head is something you’ve generated yourself. I’ve given you the information, but in reality you don’t know exactly what I saw. A lot of the detail has fallen through the cracks.

Dolphins use sound for both input and output. Everything’s in the same file format.

Because of this, there are some that think dolphins may be among the most efficient communicators on the planet. They might even be able to swap mental pictures using their echolocation skills, but we aren’t sure about that just yet.

They could also have more emotional intelligence than us. Dolphin brains contain spindle neurons, a brain cell once thought to set humans apart from the beasts. They are what allows us to feel emotions.

So they’re the culprit.

But now we know humans aren’t the only one with emotional neurons. Primates and elephants have spindle cells, as do humpback whales, fin whales, sperm whales, orcas, and bottlenose dolphins. It’s pretty cool that such a wide range of whales have these uber-intelligent brain cells.

But get a load of this. Whales have had these neurons in their brains for a lot longer than humans have. And they have more than we do. Orcas actually have three times as many spindle cells as humans, even when you adjust for size. That could mean that orcas experience emotion even more deeply than we humans can. That’s something researchers are still digging into.

By this point you might think you’ve heard more about dolphins than you’ll ever need to know. But the most important part is yet to come. I want to introduce you to a particular species of dolphin, one you’re likely to have encountered before.

The species we’ve universally decided to be the face of all dolphinkind is the bottlenose dolphin. Latin name Tursiops truncatus. That truncatus is the root of the word truncate, which means to shorten something by cutting off the end.

That became their name because the bottlenose’s beak is short and stubby compared to most other dolphins. I told you I love animal Latin names and this is another of my favourites simply because I love the idea of the first person seeing bottlenoses for the first time and going -

‘Awwww, look at its little beak!’

I’ll be making a blog post on adolphinpod.com if you want to hear any more about the scientific names of animals because it’s REALLY INTERESTING. But back to bottlenoses. They are my favourite animals on Earth and I could talk about them for hours. You’re witnessing that right now, actually.

Bottlenoses are considered a cosmopolitan species, which means they can be found in almost any of the Earth’s oceans. These are also the ones you’ll see in the vast majority of aquariums and marine parks around the world.

If you’ve been listening, you’ve probably realised that life in a tank is a universe away from what those animals would experience in the wild in every aspect. Captive dolphins do not get the opportunity to express natural behaviour, plain and simple.

I get asked all the time ‘What’s so wrong about dolphin captivity?’ because you know I’m always out there running my mouth about this stuff. We’ve already heard about their otherworldly intelligence, incomprehensible communication and undeniable culture.

But not everyone is impressed by that stuff. We don’t have a way to measure dolphin intelligence, and to a degree the science is open to interpretation. I know my view is rather favourable, to put it mildly.

So if we can’t agree that dolphins are too clever to be kept as public pets, we need to look elsewhere for evidence. For example, we could make some comparisons between the environment and behaviour of wild vs captive dolphins.

Okay, first let’s have a little look at the differences in the sizes of their habitat. For reference, the ocean covers almost 140 million square miles which is more than 360 million square kilometres.

We don’t have a global average for captive pool dimensions - because there’s nobody policing this stuff - so we’ll have to go by European standards. The European Association for Aquatic Mammals recommends that a pool for five dolphins should have a surface area of 275 metres squared, which is 2,960 square feet.

Divided by five, that means each dolphin gets about 55 square metres or 590 square feet of surface area each. That might sound like a lot at first, but let me remind you that that’s a minuscule fraction of the potential room to explore they’d have in the wild.

What about depth I hear you ask? Like before, a pool for five dolphins has to have a depth of 3.5 metres, which is just over 11 feet. Let’s just have a look at the average depth of the sea. It’s 3700 metres, which is well over 12,000 feet.

That’s not the maximum, it’s the average. In the wild, the average dolphin gets to swim in water two MILES deep. In captivity they get three and a half metres. 11 feet instead of two miles, for their entire lives.

I bet they miss it, too. A wild dolphin can dive to 1,000 metres or 3,300 feet and stay under for almost 15 minutes. Deep dives are a normal part of a dolphin’s everyday life. In the wild, at least.

So now we know how deep they like to go, how far do wild dolphins swim in a day?

A scientific paper published in Current Zoology in 2017 puts that distance between a minimum of 12 kilometres, or 7.5 miles, and a top range of 105 kilometres which is 65 miles.

I’ve done the maths on this, and in a pool of the size I described earlier, for a dolphin to swim the minimum distance it would out in the wild it would have to do more than 175 laps of the pool every day, To hit the maximum distance they’d have to swim in circles over 1500 times.

Now I’d like to compare the actual activity of wild dolphins to those stuck in captivity. When we study animal behaviour we can track what they do over a long period and come up with what we call an activity budget. We identify their most prominent behaviours and work out what percentage of their time they spend engage in each.

55% travelling

20% milling (which is leisurely swimming, not making flour)

17% feeding

7.5% socializing

0.5% resting

So about 75% of a wild dolphin’s time is spent swimming. More than half of it is spent moving at speed, whereas 20% is slower and less purposeful.

Let’s compare that to a captive dolphin now. I have to say, it was much harder to find data on captive dolphins which is ridiculous because the animals are right there, 24 hours a day ready to be studied. We could have had this data nailed down 100 years ago. It’s almost as if they aren’t willing to tell us how vastly different captive life is to freedom. Weird.

Luckily I found a paper in the International Journal of Comparative Psychology detailing the activity budgets of seven dolphins at a facility the scientists involved refused to name. Interesting.

Their dolphins spent about half a percent of their time swimming fast, which is close to a 100% reduction from the amount they do in the wild. Oh, and they rested 10 times more in captivity than they do in the open ocean.

Does that not ring alarm bells for you? That these animals that have been kept on display for the entirety of our collective living memory without being allowed to behave how they want to? How they need to?

And we haven’t even touched on the social aspect of dolphin life. Do you know how wild dolphins interact? Just like us, they’re obsessed with social networking. That’s the biological term for it. You can go online and read a legitimate scientific paper titled “Social networking in dolphins”.

I wouldn’t bother though, it’s quite wordy. And of course they aren’t using the internet or computers or phones. It really boils down to this. Dolphins spend all their lives swimming around and meeting other dolphins.

They like being in groups but their societies are fluid. It’s not like human society. I can’t just wander into a neighbour’s house and announce I’m joining their family. Not again, at least.

But dolphins are way more social than us and making memorable connections with perfect strangers is vital to their survival.

A pod of 12 might bump into a group of three and make a team of 15. Five of them might then go one way to follow an anchovy shoal while the others head off to scour the seabed for animals under the sand. That splinter group might meet another seven and all join a multi-species feeding frenzy together.